Urban Fantasy, Hard Sci-Fi, Epic Fantasy, Space Opera, Steampunk, Soft Sci-Fi, Dark Fantasy…alas, the list goes on in yet more attempts to fit a many-sided shape into a dragon-shaped hole.

The label of fantasy means the imagining of something impossible or improbable. This definition would seem to me to encapsulate all of the genres above and many others, which begs the question, is there really any need for a separate categorisation at all, let alone the hundred or so sub-sub-sub categories?

In particular I am debating the need to separate out Science Fiction from the wider genre of Fantasy.

Before you Sci-Fi fans aim your M41A Pulse Rifles in my direction, please let me expand.

If you are a newbie to Fantasy then you may not yet fully appreciate the extent to which readers and geeks across the world will defend their particular genre, flaming sword of Darkthor held up against the darkness of the Blaster rifle of Death-Tech.

Before getting swallowed by the Sarlacc of styles, the catacombs of category, imagine, if you will, a world where goblins and aliens rub shoulders without us having to assign some random, barely relevant, yet highly specific label to it.

I recently contributed to a fascinating forum discussion on Goodreads on the nature of Fantasy and Science Fiction as genres. The question posed was whether they should join forces and become one, giant uber-genre, or remain separate, forever destined to confuse and confound the afore-mentioned fantasy newbie. Being a fan of both fantasy and science fiction, my reading habits leaning towards more traditional Fantasy while my writing has a more Sci-Fi / contemporary bent, I thought this a highly relevant topic for debate.

What’s the point of having genres in the first place?

Readers shopping on-line or browsing a bookstore require genres in order to make an informed choice about what they are going to read. I too find it useful to have certain labels to guide me in the right direction. One such label is the author name. I know the authors I love and will get their books without reading the back blurb, confident that I’m going to enjoy it.

When I am looking for a new book to read, it almost invariably comes about from a recommendation. I don’t ask what the genre is in advance, and it isn’t really important at that stage. If it’s from my mum, I stock up on happy pills and prepare myself for some serious ‘literature’. If it’s from my brother, it’s more than likely to be fantasy in one guise or another. If it’s from my other brother, it’s probably Edge magazine, or…nah, just Edge (he’s not a big reader). Regardless of genre, the first question is ‘Is it any good?’ So genre is useful, but it doesn’t define what I read. In fact staying within the virtual bricks and mortar of our one or two pre-defined genres of choice would mean I would miss out on the treasures that might be found beyond the walls.

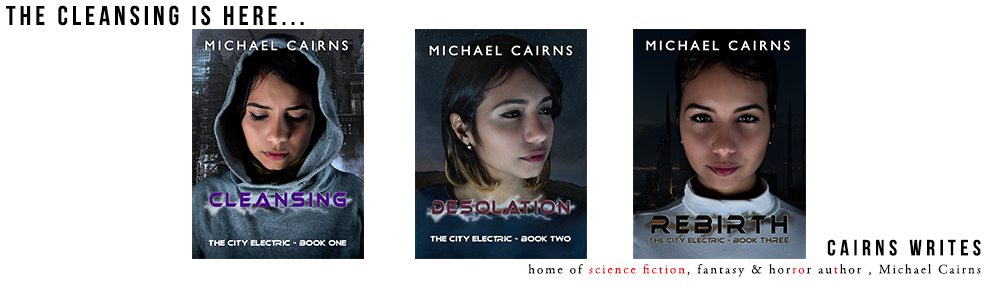

From a writer’s perspective this excess of categorization does little to enhance the elegance of the publishing process. My publisher, aka my wife, had the joyful experience recently of researching the Amazon genre list for the release of my new novella.

She had to check with me whether some of the sub genres were actually real or perhaps an in-joke with the Amazon Fantasy crowd designed to drive her crazy.

Having become convinced that they were genuine, she then had to figure out exactly what the key features of each genre were. Having reached the ‘New adult with a car but no girlfriend and only average prospects fantasy’ tag, she actually ate the Mac before running gibbering down the garden. After hours of coaxing with a mug of tea and copies of Shakespeare, she finally came out, but still gets the shakes when I mention the ‘G’ word.

My wife is often the first to remind me that it is essential that we are very specific when it comes to marketing and promotion and she’s entirely right. Knowing our readership and understanding what makes them tick is, particularly in this era of self-publishing, a must. I am, however, not convinced that the degree of specificity emerging in our labeling of art adds more than it jeopardises.

The more specific the genre, surely the greater the chance is that the reader may feel let down or betrayed should the author stray from the blueprint and this is a real concern. Keeping our promise to the reader is essential if we are to maintain a trusted brand. Some of my own books, for example, exist in space, with aliens and spaceships. However, there’s also magic and some hippy-shit thrown in as well. Why? Because I think it’s what the story needs and I’m not sure sacrificing good story to fit with marketing conventions is ever a good move.

The idea that by putting just the fantasy tag (and nothing more) on my book I may inadvertently drive away, or not attract in the first place, lovers of space ships is a bit saddening. That it will also drive away lovers of romance and soul-searching coming-of-age stories is also a shame, because there’s some of that in there too.

So, whilst I can recognize and appreciate the value of genre, it also strikes me as maddeningly limiting.

In an ideal world, if I went to buy a fantasy book, I could expect one or more of the list below:

- Dragons

- Magic

- Space ships

- Werewolves

- Rings (always with the bloody rings)

- Swords

- Snakes

- Elves

- Planets

- Very tough men

- Very tough women

- Priests

- Pickpockets

- Castles

- Horses

- Crazy-ass guns

- Vampires

- Succubus (every book should have succubus really. Where’s the bad?)

- Giants

- Trees talking/walking/doing the boogie

- Evil empires

- Tyranny on an intergalactic scale

- Shnoos.

I guess I don’t get why space ships are ok, but vampires aren’t; why elves are fine but giant killing robot things not so much.

So let our improbable imaginings be named Fantasy and let’s be done with it. Let us focus on taking our readers on the journey the story dictates whilst having the freedom to do so.